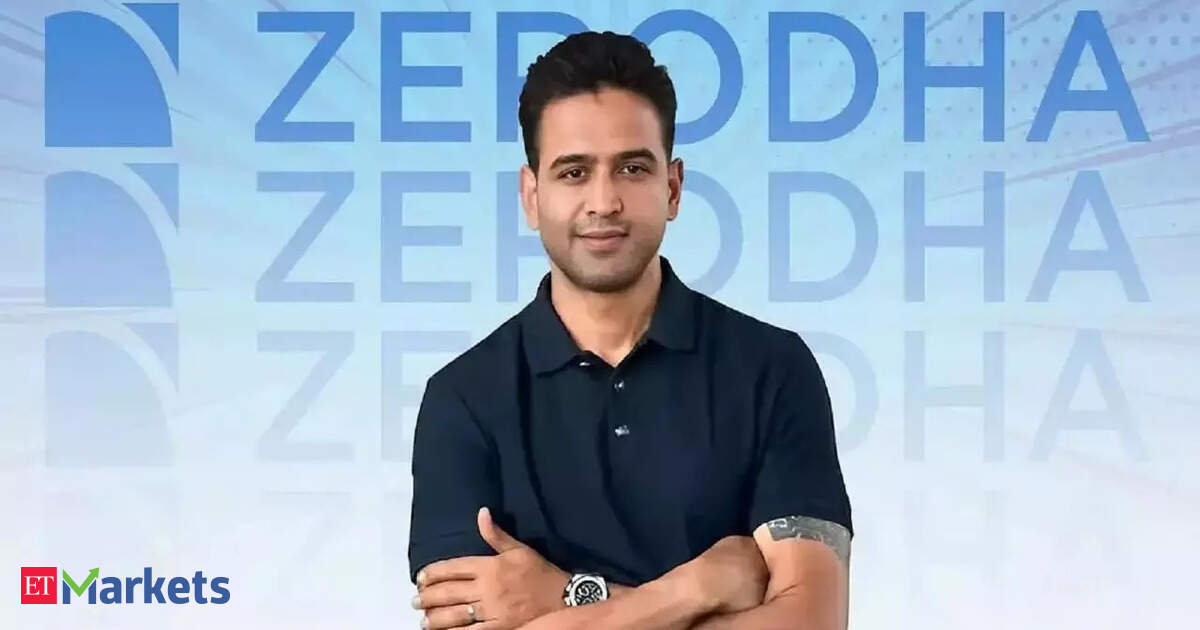

In a post on X, Kamath recalled a conversation with a veteran from private equity who had evaluated a broking firm in 2008 but backed out. “The revenue was concentrated in just a handful of clients,” the investor had said—something that spooked them. At the time, a very small group of traders generated most of the exchange turnover. “This was a lot worse back then,” Kamath noted.

Fast forward to today, and while the number of retail traders has increased, the problem hasn’t gone away—it has only shifted shape. “For us, it’s over 80%,” Kamath said, referring to the share of Zerodha’s revenue that comes from just two F&O contracts: Nifty and Sensex. He added that this trend is true for most brokers in India.

That’s a risky dependence. “That means one change can wipe out a big chunk of our revenues,” he warned.

What makes it worse, Kamath pointed out, is the lack of alternative revenue levers in India. There’s no payment for order flow (PFOF)—a controversial but lucrative practice in countries like the US. Cryptocurrency trading is largely off the table. And new rules such as quarterly fund settlement, which require brokers to return all unutilized funds to customer accounts every quarter, add operational stress.

“I wonder why the brokerage business looks so sexy from the outside,” Kamath quipped.His reflection is a rare public unpacking of how regulatory limits, market behaviour, and structural dependencies create a fragile business model—even for India’s most successful brokerages.